As I was driving in to Al Maha, my driver laughed when he heard that my interest in heading out into the desert was the wildlife.

“There’s nothing out there,” he said, shaking his head.

How wrong he was.

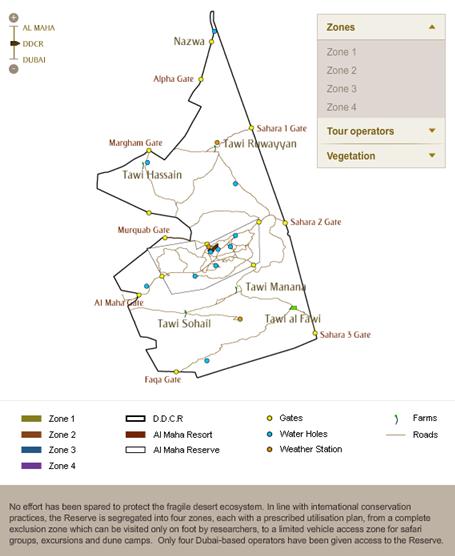

Al Maha is situated inside the 225km2 Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve (DDCR) and operates in tandem with a massive conservation effort to help bring back a host of native species to the deserts they once thrived in. And that was my primary interest in the region. The beauty of the desert was just a happy, happy bonus.

The UAE has three key ecosystems – desert, marine and mountain. And, though Dubai is fringed by mountains none of them are inside its borders. So, Dubai’s ecology is partly marine but mostly desert. And in past years, exploitation of those resources has pushed a heap of the Emirates’ most iconic and endemic species to the brink of extinction (and some of them over).

You can read all about the Conservation Reserve’s history and aims here but here’s a potted summary.

In 1999, 27km2 was set aside as conservation reserve, 70 endangered Arabian Oryx (Al Maha) re-introduced, 6000 trees planted and a seed-bank commenced and a luxury resort nestled into the dunes. After four years of intensive assessment, lobbying and profile building thanks in large part to all the visitors that the resort attracted, the area was increased to 225km2 (5% of Dubai’s land area) and a year later more at risk wildlife was re-introduced. With assured food and water, the population of oryx steadily grew to 500 within the DDCR and a range of native gazelle species also thrived. conservation work saw a total of 37 bores set up and plantings expanded to some 35,000 trees planted.

It’s the only example I’m aware of where a conservation program significant enough to get an IUCN tick (the DDCR was granted protected area status in 2008) has been born out of a commercial/tourism project. Usually it’s the other way around.

Lawrence-of-Arabia told me that recent research indicated the DDCR ecosystem was supporting at least 70 plant, 17 mammal, 26 reptile, 126 bird and 115 insects species.

So much for there being ‘nothing’ out there!

Of those the most famous are the Al Maha themselves — Arabian Oryx. They were definitely on my hit-list of creatures to see but I was also hoping for an Arabian Red Fox, Ethiopian Hedgehog and the Arabian Hare. I got three out of four. Oryx I saw aplenty, a fox I saw for a momentary heartbeat, and the hedgehog I saw on my guide’s smartphone. In three years he’d only seen one because of their shy, nocturnal habits.

I probably saw about two dozen different creatures in my three days, but then, with 50C daytime temperatures outside of my beautiful little human habitat and the promise of vipers at night, I confess to not really wandering very far. Next time I’ll be more prepared. And I’ll go in cooler weather.

But this meant the opportunity to head out into the desert in air-conditioned comfort for an up-close look a the conservation work they were doing was trebly valuable.

So… on day 2 of my visit, I was incredibly fortunate to get a private tour of the behind-the-scenes conservation area. It was only later I discovered that Lawrence-of-Arabia had had to do some serious talking to get me the access he delivered so effortlessly. He took me well off the beaten tourist trail to one of two areas where their most intensive conservation activity is underway — the creation of a massive ‘oasis’ ecosystem hidden in the valley between mountainous dunes.

Here the conservation team have established massive groves of palms and other native trees (to provide future fodder for the animals in the whole reserve) and the beginnings of some kind of aquaculture. Given fish aren’t exactly native to desert oases, I have to assume it’s a flora- or crustacean-based aquaculture. Some kind of weird desert crab?

Or maybe it’s just really big so that it never runs dry.

- Date palm laden with dates – staple diet for the Oryx

- Masses of desert plantlife growing at the oasis

- Revegetation getting started

The massive fences that contain and protect the DDCR interested me because of their backwards facing orientation. Normally in wildlife reserves the overhang faces outwards, to keep predators out. In the case of the DDCR the fences I saw all faced inwards and Lawrence explained that the desert drifts built up so quickly that animals could simply wait for the sands to mound up and ‘walk out’ if not for the inwards-facing overhang. For the same reason, they bulldoze the perimeter regularly to keep nature’s ladders at bay.

By the way, humans re classed amongst the ‘predators’ given the extreme value of the Arabian Oryx not so very long ago. The armed guards at the limited access gates into the reserve certainly weren’t there to keep the human visitors safe…

As is always the case with managed conservation programs, this one faces its challenges. By fencing the animals in they interrupt their natural migration patterns and limit their ability to source natural food sources. By provision of supplementary feeds to compensate, they risk changing the animals’ natural behaviours and permanently affecting their metabolism.

As is always the case with managed conservation programs, this one faces its challenges. By fencing the animals in they interrupt their natural migration patterns and limit their ability to source natural food sources. By provision of supplementary feeds to compensate, they risk changing the animals’ natural behaviours and permanently affecting their metabolism.

Then again, with the human world encroaching as steadily as the sands, maybe they need to start altering their natural behaviours in order to survive.

Tomorrow… a bit more on the Arabian Oryx (Al Maha).

Leave a Reply